NOTE: A version of this article was originally published on the PhotoED blog at JON STUART: Stillwater.

Wetlands. As the name suggests, they’re not water but they’re not completely land, either. In fact, they’re the places you often drive past while you’re on your way somewhere else. A lot of Canadians only ever see wetlands through a car window. Or not at all.

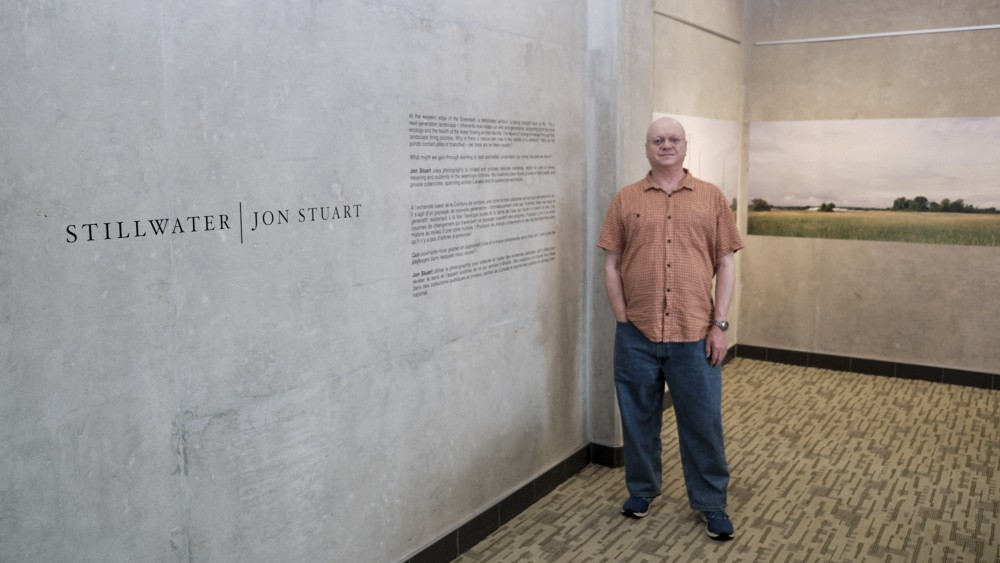

Fortunately for us, Ottawa photographer Jon Stuart slowed down long enough on his daily mid-pandemic bike ride to take a closer look at an elm tree growing where it shouldn’t – in the middle of a wet field. And he went back again and again with a large format camera. His exhibition at the Shenkman Arts Centre is the result.

Stuart learned that the elm, a local landmark, was sitting in the middle of land that had originally been drained for farmland but is now part of the flood zone around Ottawa’s light rail line. Conservation groups are working with local government agencies to encourage recovery of the wetland which is now showing signs of new plant and animal life.

A graduate of the School of the Photographic Arts: Ottawa, Stuart used a 4”x5” view camera – at times paired with a 6x17cm film back for panoramas – to allow for the creation of the large, highly-detailed vinyl and framed prints on display in the gallery. Prints this large have a push- pull effect on viewers: you need to stand back to take them all in, but you’ll want to get up close to appreciate everything that is going on. (Do it. It’s very satisfying.)

Jon Stuart

On display until October 31, Stillwater is a chance to learn more about the delicate ecology of suburban spaces and to take in beautiful landscape photography with a purpose.

Stillwater by Jon Stuart

LaLande + Doyle exhibition space at the Shenkman Arts Centre

245 Centrum Boulevard

Ottawa, ON K1E 0A1

Until October 31, 2023

Artist talk 17 October 2023, 6 pm