Àbadakone (Algonquin for “continuous fire”) is the second exhibition “in the National Gallery of Canada’s series of presentations of contemporary international Indigenous art, features works by more than 70 artists identifying with almost 40 Indigenous Nations, ethnicities and tribal affiliations from 16 countries, including Canada.”

According to the National Gallery, “the title Àbadakone was provided by the Elders Language Committee of Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg. They felt that its connotation of a fire within each artist that continues to burn would be an appropriate title for the second presentation of this ongoing series of exhibitions showcasing Indigenous art from around the world.”

Indigenous art and culture is drawing a lot of attention in Canada and other countries dealing with the history and ongoing impacts of colonization of the “New World” by European powers.

I found the exhibit exciting as it opens up a broad range of discussions that are important not only for Indigenous people, but for anyone who has an interest in place, identity, the construction and evolution of culture, and the importance of narrative for creating and bearing meaning. The introduction at the entry to the exhibit indicates that the broad theme behind its curation is one of “Relatedness, Continuity and Activation.” In brief, this refers to the interconnection of all things, the links across time and generations, and “how an artist animates a space, an object, or an idea through performance, video or viewer engagement.”

(All images taken on my cellphone.)

For me, there were several threads that ran through the exhibit, particularly the challenges of:

colonization;

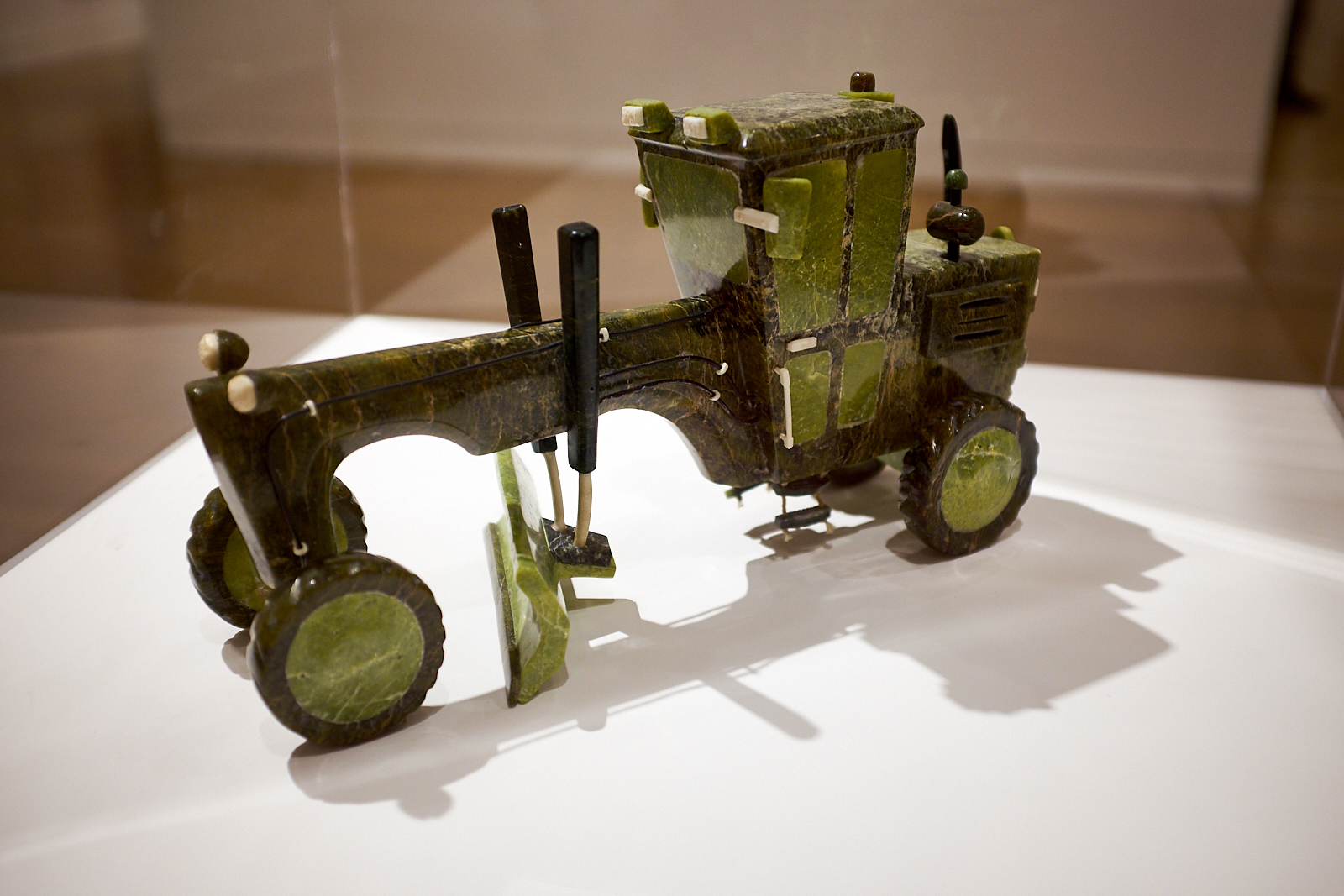

industrialization;

globalization;

environmental degradation;

technology;

migration; and

tradition.

Without taking anything away from the specific issues and questions facing the Indigenous artists who created these works, it seems to me that many of the challenges are also faced by non-Indigenous people. As a result of the challenges I’ve listed above, very few of us can simply take for granted the place where we stand, the identities we have inherited, the histories that have shaped us or the futures that lie before us. In a time of profound uncertainties, it will be important to draw selectively on our knowledge of the past, on our best understanding of our times and on the most promising paths forward. It is fascinating to see that while Postmodernism rejected meta-narratives, we continue to need overarching stories to interpret the past, create meaning in the present and have hope for the future.