Two examples of the use of print and pattern come to mind immediately, one on either side of the Atlantic: Burberry's trademark scarf (below left, UK) and the Hudson Bay Company's signature blanket (below right, Canada).

Both patterns are immediately recognizable and both have been imitated. The two companies have worked hard to use the pattern to identify a unique product line that denotes tradition and high-quality, although sometimes with unintended effects. Burberry had to endure years of its pattern being associated with anti-social behaviour ("Burberry versus The Chavs") and Hudson's Bay has been accused of appropriating Indigenous culture ("HBC’s ‘Colonial Barbie’ comes with some baggage"). Both companies have extended the use of their pattern to other items.

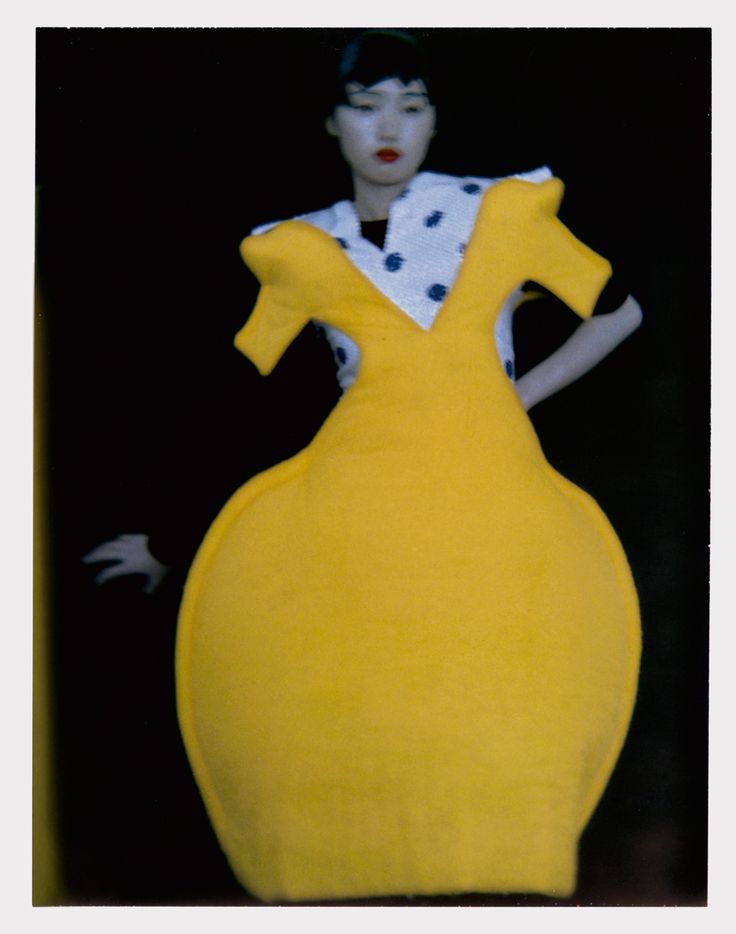

Mary Katrantzou

The article cited on Greek fashion designer in the course materials does not seem to be available anymore. There is, however, a useful review of her 2011 Spring Ready-to-Wear show in the online edition of Vogue (accessed 22 August 2017).

As Katrantzou works on her creations she "designs in 3-D"—that is, she plans the form, volume and drape of the garment at the same time that she develops the pattern / illustration that will be screen-printed onto the fabric.

"I thought I was going to do a collection about the seventies photographs of Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton: all those women in incredible rooms. But then I started to look at the rooms more, and suddenly, I was putting the rooms on the women instead!"

By this, I think Katrantzou meant that rather than have women serve almost as visual accessories within exotic locations, the locations could serve the women by drawing attention to their own appearance. She achieved this through the design process described above that allowed her to digitally print striking architectural images on to the clothes she created. The clothed woman is the centre of attention, not the backdrop in which she is placed (slideshow of garments in the 2011 collection, accessed 22 August 2017).

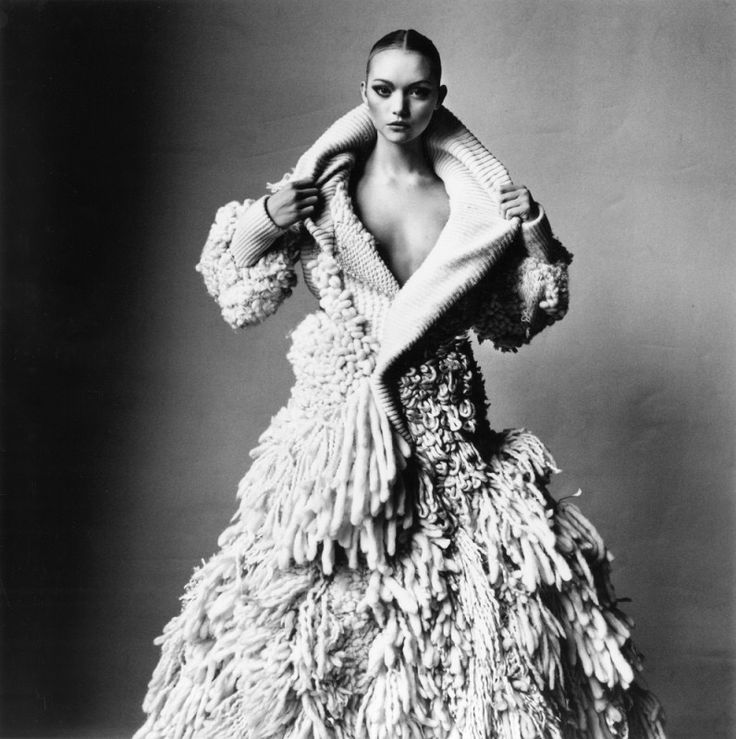

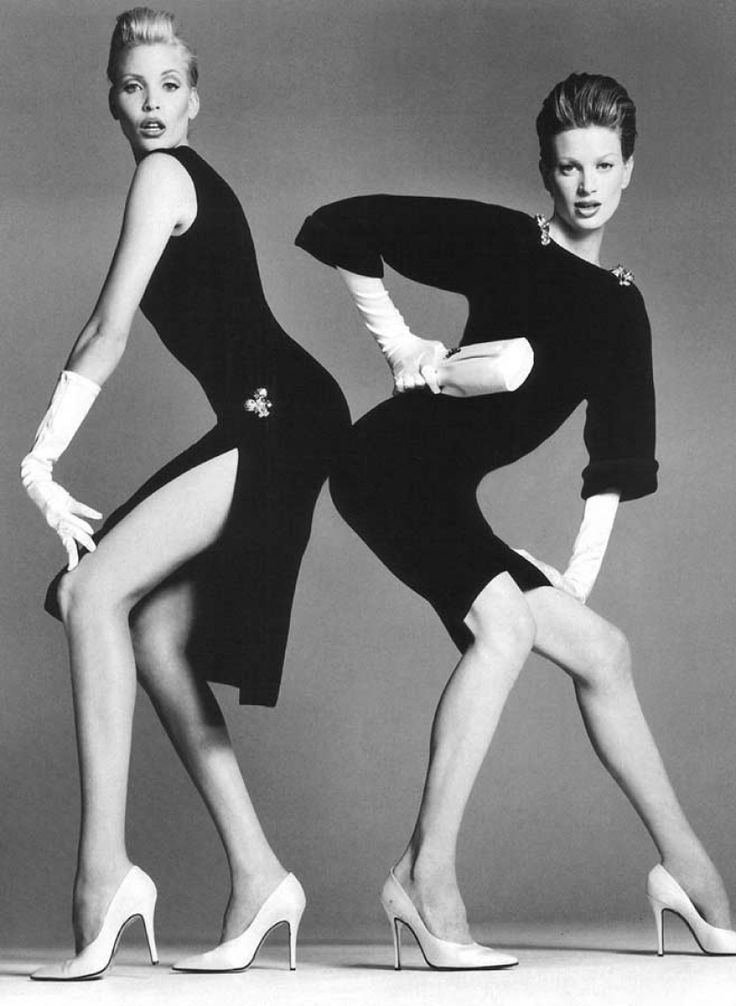

Examples from Mary Katrantzou's Spring 2011 collection