Anthropocene opened in two complementary versions, one at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa and the other at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto. The title of the project is a still-contested term that refers to a new geological era where “…human-kind has caused mass extinctions of plant and animal species, polluted the oceans and altered the atmosphere, among other lasting impacts” (Stromberg, 2013)

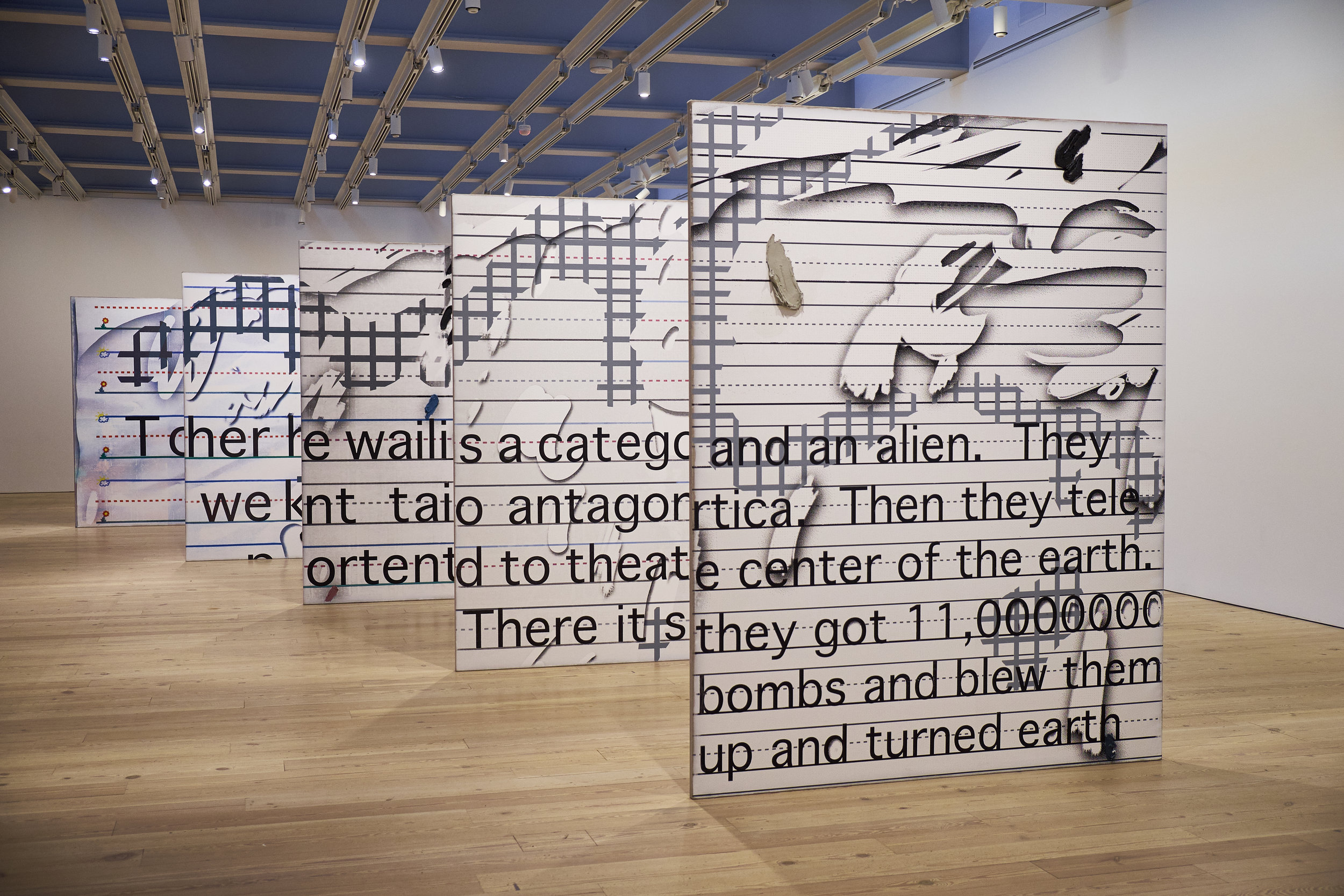

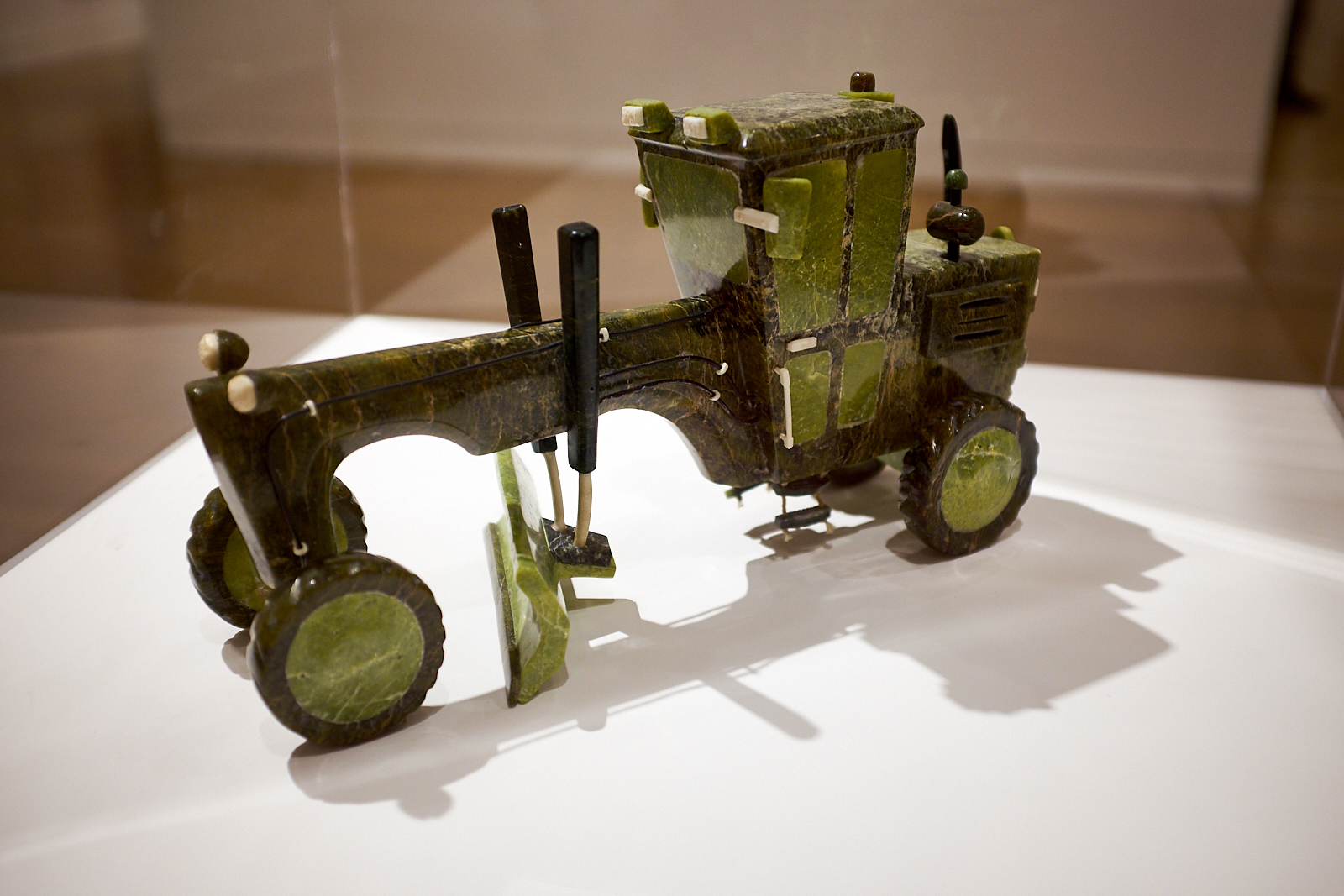

The project is a large-scale multimedia production comprising still photography, video, a movie, augmented reality installations and a book. It is in line with Burtynsky’s other work both with and without collaborators: bold, richly layered, large-format photographic prints that make viewers stop to look at things that are worrying.

Anthropocene is very much a project, not only in the sense that it combines the talents of several Canadian artists, but also because it uses art to advance particular ethical and political positions. Although the artists—in words, at least—are careful to lay out information rather than to preach their stance on human impact on the environment, the conclusion of their work could not be clearer. It is possible to imagine a series of images showing the benefits of resource extraction for humanity—or even the utter dependence of our economies on fossil fuels—but that is not what has been done here. Anthropocene is a damning artistic documentation of wholesale exploitation, waste and degradation for the planet and its lifeforms.

I have seen and appreciated Burtynsky’s photographs for a number of years but I find that I am now looking at them differently since reading Stephen Shore’s (2013) brief book. Although I have always appreciated the beauty and content of the images it is only now that I am looking at them as photographs. The images play with framing, scale and geometry in such a way that it is not always clear what you are looking at.

Many of the photographs are printed so large and cover such a vast area that you must look at them twice: once from farther back to take it all in, and then an implied invitation to draw closer to peer at details and to orient yourself in the frame. Sometimes, for example, it is only at nose-distance that tiny blobs of colour reveal themselves to be heavy vehicles in an immense open-pit mine. By being invited into a two-step viewing, I found that my reaction was often to be impressed by beauty at large-scale, and to be shocked by the detail as I moved closer and more fully took in what I was seeing.