[Note: the Oxford Art Online website has not been accessible to OCA students for some weeks while the contract is being renegotiated. The notes below were made before access to the website was closed.]

Whitney Davis, ‘Communication theory’

http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T018901

Davis provides a broad outline of communication theory’s major concepts and elements. Important distinction to be made between “information” (understanding that can be derived from perception) and “communication” (the intentional delivery of a message). It is interesting to see how authorial intent can pop in and out of discussions in the art world, depending upon which theorist happens to be invoked.

Communication, according to Roman Jakobson’s scheme, has six major factors: ‘addresser’, ‘addressee’, ‘message’, ‘code’, ‘context’ and ‘contact’. Code and context are particularly important, for they describe the interpretive framework within which communication can occur. Too great a gap in code or context between addresser and addressee, and communication will be ineffective or impossible.

Stephen Bann, ‘Semiotics’

http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T077528

Term referring to the analysis of signs and their use. Major theorists are Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914), Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913) and Roland Barthes.

“Saussure has been called ‘the father of modern linguistics’. He drew a crucial distinction between the linguistic system and its actual manifestations in speech (between ‘langue’ and ‘parole’). He further distinguished between the referential dimension of language, the ‘signified’ (‘signifié’), and the phonic substance of speech, or visible traces on the page, the ‘signifier’ (‘signifiant’).”

Jan Mukarovsky later translated Saussure’s linguistic insights into the esthetic realm to distinguish the ‘sensuously perceivable “work-thing”’ and the ‘aesthetic object’ existing ‘in the consciousness of the whole collectivity’.

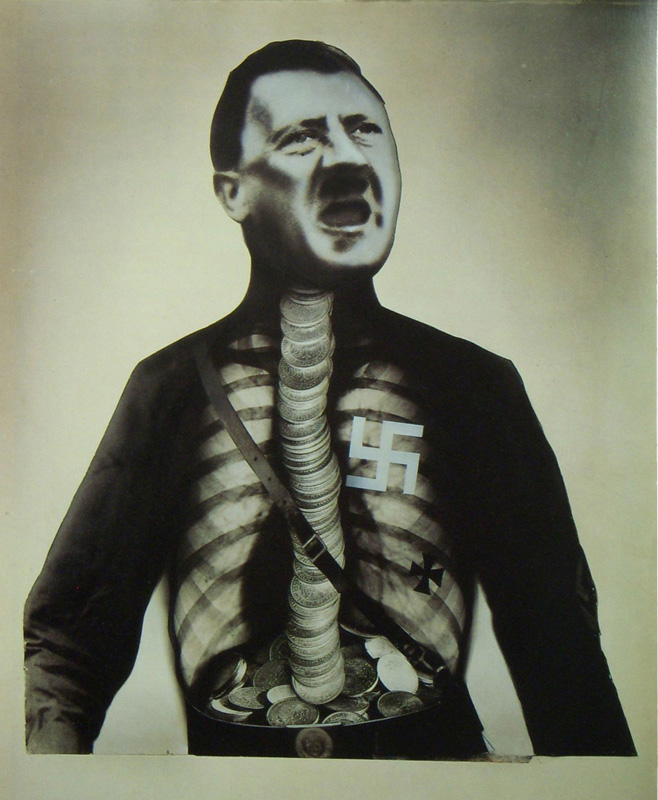

Peirce developed a taxonomy of signs to all things and began to classify them by a tripartite division: icon, symbol and index: “the icon relates to its referent by resemblance, the symbol by convention and the index by existential connection.”

Penny Sparke, ‘Design’

http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T022395

Current sense of “design” originated with expansion of industrial revolution and the related separation of of conception from manufacture. Early on, design was largely embellishment or decoration of objects produced by mass processes, so schools of design were primarily interested in developing the drawing skills of students. The emphasis on style and decoration helped to fuel consumerism and sparked a reaction among people like John Ruskin, William Morris and what came to be known as the “Arts and Crafts” movement, “epitomized by such tenets as ‘fitness to purpose’ and ‘truth to materials’.” The movement helped give greater place to ethics and esthetics in design.

Another impact of the Arts and Crafts movement in the early 20th century was the “democratization of design” and the rise of schools and guilds dedicated to it and related principles. Significant figures and groups in this modernist period include Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, the Wiener Werkstätte, C. R. Ashbee and his Guild of Handicrafts, Peter Behrens, Richard Riemerschmid, Henry Van de Velde, and the Deutscher Werkbund.

In the Americas, as industrial production expanded into assembly line mass creation of consumer goods, standardization was the rule. This was not satisfying to consumers for long, so there was a move to greater esthetic detail on the one hand (consumer demand) and the explosion of advertising on the other (consumer awareness). Although some of the same trends could be seen in other parts of the world, “designers in Europe during the inter-war years continued to be more interested in the metaphorical and aesthetic implications of contemporary life and in evolving objects that were appropriate to it” (Le Corbusier, Bauhaus).

Modern movement and later the “International Movement”: “applied to the architecture of simple geometrical forms and plain undecorated surfaces, free of historical styles, that developed mainly in Europe in the late 19th century and the early 20th prior to World War II” (Modern Movement).

Margaret M. Smith and John Newel Lewis, ‘Book illustration’

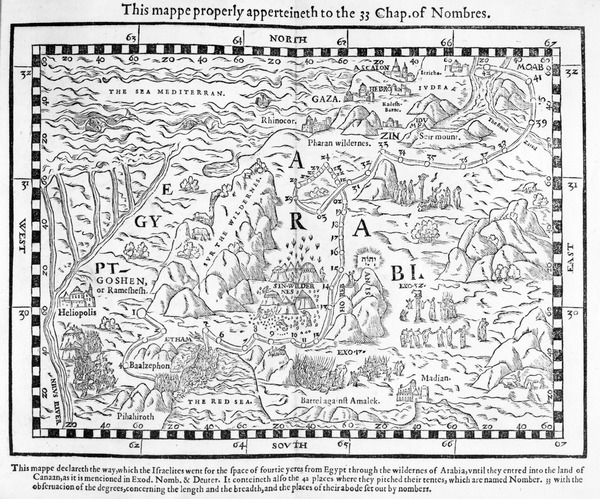

Originally, all illustration was created by hand. Later techniques included woodcuts (before 1600; allowed both text and illustration on a single page), copper engraving (second half of 16th century) and other “intaglio” techniques (17th century; printmaking techniques in which the image is incised into a surface and the incised line or sunken area holds the ink). It was difficult to employ both intaglio and movable type on a single page, so text and image were usually on separate pages. Wood engraving was popular in the 18th century, while colour printing and lithography appeared in the 19th century.

![Train Window - Green Pine{车窗-青松]. Zhang Xiaogang 张晓刚2010](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5224bdefe4b0f7b35c282f4d/1488939247018-YFOP2WCTXKYP4TKMJGKY/55e1ef71-eacf-4603-88f0-e75da8552b87_l.jpg)